Many of us have probably heard of the term “adrenal fatigue.” Endocrinologists and Western medicine typically take the stance that adrenal fatigue does not exist. It’s true that the term is not recognized in the medical literature. Typical symptoms associated with adrenal fatigue include tiredness, poor sleep, anxiety, cravings for salty or sweet foods, or otherwise feeling run down and lousy, making it hard to get through the day. The issue with the term “adrenal fatigue” is that it implies the body is unable to make enough cortisol due to “fatigue” of the adrenal glands. While low cortisol is a player in the collection of symptoms associated with adrenal fatigue, the decreased output is due to dysfunction within the whole stress response system, not within the adrenals themselves. The new term being adopted is Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal-axis dysfunction or “HPA-axis dysfunction” for short. The HPA-axis is essentially your body’s stress response system and too much stress can throw it off. This term better explains the underlying physiological distress that underlies the symptoms typically associated with adrenal fatigue. However, “adrenal fatigue” is certainly easier to say. If your adrenal glands truly cannot make enough cortisol, you might have Addison’s Disease, an autoimmune condition that destroys adrenal tissue.

Stress Starts in the Brain.

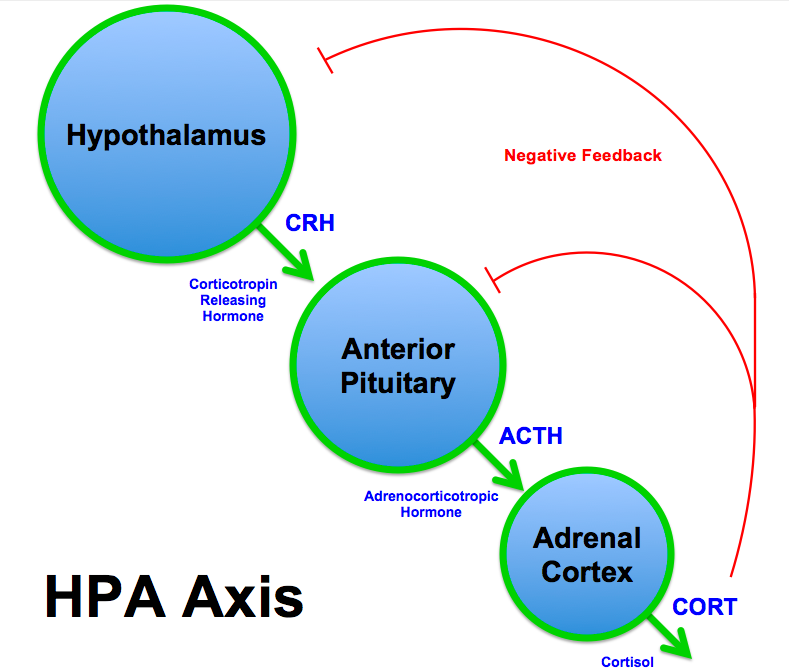

The hypothalamus and pituitary are endocrine glands that reside in the brain. The hypothalamus is constantly monitoring internal and external stimuli and is at the core of the stress response. When the hypothalamus senses a stressor (this could be anything from a negative thought to an injury, to a gut pathogen) it sends a message to the pituitary that then sends a message to the adrenal glands to produce cortisol, which then helps us deal with the stressor. More specifically, the hypothalamus will release corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) that signals the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then acts on the adrenal glands to tell them to make more cortisol. It’s a team effort! This means that if the amount of cortisol your adrenal glands are producing is too high or too low, it is usually a result of the signaling happening between the three glands and is not a direct reflection of the health of your adrenal glands alone.

The Ideal Stress Situation

Ideally, when we are faced with a stressor, the HPA-axis is activated to help us produce more cortisol to deal with the stress, the stressor is resolved, and things go back to normal. During this process cortisol sends negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary to let the glands know the job is taken care of and they can stop sending messages to produce more cortisol. But this ideal situation isn’t very common.

Modern Society = Chronic HPA-axis Activation

Stress is unavoidable and part of being human. For example when a loved one passes, we are under stress, but death and loss are part of our natural lives. Avoiding stress isn’t the objective. The problem is when we are faced with too many stressors for too long, which is all too common in modern society. Think deadlines; long commutes; noise, light, air, and other environmental pollution; poor sleep induced by work anxiety; financial instability; disconnection and lack of community; reliance on processed foods; being too busy too often; trying to be in too many places at once; lack of down time; too much sitting; too much screen time; the list goes on.

Our stress response system is designed to handle acute stressors. This means stressors that come on suddenly and resolve relatively quickly. It was not designed to keep up with ongoing chronic stress that never resolves. In the case of chronic stress, the HPA-axis signaling never has the opportunity to slow down due to the constant influx of stress. Overtime, this leads to dysfunctioning within the system. This is an unfortunate reality of our modern lives.

But There’s Hope!

Stress is a perception. How stressed you become is highly dependent on how stressful you perceive the situation to be. Remember, the hypothalamus is in the brain. If you can’t directly reduce the amount of stress in your life, you have the power to change how you think about it. Holocaust survivor Viktor E. Frankl said in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” He is also quoted as saying, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

It’s important to remember that stress is not limited to mental/emotional factors. Gastrointestinal infections or bacterial imbalances in the gut are both sources of stress that can ultimately ripple out and affect the whole body. Intestinal permeability; continually eating foods you are sensitive to; consumption of an inflammatory, high-processed-foods diet; excessive sugar intake; use of toxic body care and cleaning products; injuries; structural imbalances and muscle strains; and viral infections can all activate the HPA-axis. While you might not be able to think your way out of a gut pathogen, you can still be proactive by addressing any gut dysfunction, eating a whole foods diet, using only non-toxic body care and cleaning products, giving yourself time to recover from injuries, and addressing any postural/structural imbalances, among other strategies. While these things contribute to the body’s stress load, the way you think about them has an impact too. If you tell yourself things like, “Oh my God, I have so much gut dysfunction. This is so terrible. I’m so messed up. I’m doomed,” that sends your brain an entirely different message than if you were to say, “Wow! I’m so relieved to finally find out that my gut dysfunction could be contributing to the other symptoms I experience. Now I have more direction on how to heal. I can work with this!”

Can you feel the difference?

Here’s a great TED talk on making stress your friend.