What is Cortisol?

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid steroid hormone synthesized from cholesterol and made in the adrenal glands. Cortisol is dubbed the “stress hormone” because one of its major jobs is to help us mobilize during stressful situations. Since cortisol is termed the stress hormone, it might be intuitive to think the less of it the better. However, cortisol has functions beyond the stress response and we need it to survive our daily lives. High cortisol can lead to many unwanted symptoms, but low cortisol is also an unfavorable, and potentially dangerous, situation. As with most things in life, it’s about balance. We want to be able to modulate its release as needed rather than have chronically high or low levels.

Cortisol has a Rhythm

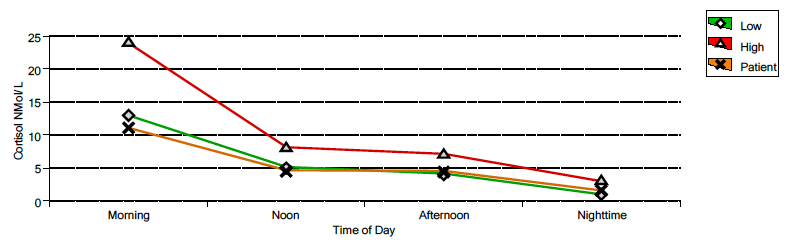

Cortisol spikes up in the morning and then slopes down throughout the day being lowest at night. Since cortisol encourages us to be more alert, this pattern helps give us a boost of energy in the morning when we need it and then helps us relax and fall asleep at night. The image below outlines the normal ranges and pattern of cortisol throughout the day. Notice that the lines (red = high end of range, green = low end of range) are highest in the morning and lowest at night reflecting cortisol’s natural rhythm. This graph displays a suboptimal cortisol curve (orange line) with measurements below the range during the first part of the day and then low in the range the second part of the day. These are my test results from 2015. Ideally, values would fall between the red and green lines.

Testing Cortisol

Because of cortisol’s rhythm, when testing, it’s important to collect samples from multiple time points throughout the day. It’s common practice to test cortisol by doing just one blood draw. If only one time point is sampled, abnormalities can be missed. Cortisol might test “in range” at one time point, but thereafter it might plummet down or skyrocket up. This method of measuring can make cortisol seem like it’s okay, when really it’s not. It should also be considered that blood draws are stressful for many people and therefore may have the ability to make cortisol appear higher than it is. Using saliva or urine testing avoids this issue.

Urine testing can also provide additional information by looking at both total cortisol production and free cortisol. Free cortisol is “freely” available and usable by the body. Total cortisol includes both free cortisol and cortisol that is bound to proteins and not usable by the body. Saliva testing only looks at free cortisol. In some cases, total cortisol production is low (meaning the body isn’t making very much), but free cortisol is high (meaning the little bit that is being made is hanging around longer). If we only looked at free cortisol in this situation, it would be logical to conclude that we need to lower cortisol. However, in this case, lowering cortisol could make someone feel worse since they aren’t actually making a lot of it. A common reason behind this scenario is hypothyroidism. You can also see cortisol patterns where there is high total cortisol production but low free cortisol available. If we only looked at free cortisol, we might think we should try to raise it. Again, this could make someone feel worse because they are actually already making a lot of cortisol. One possible reason behind this pattern is blood sugar dysregulation.

Functions of Cortisol

Breaks Things Down: Through a process called gluconeogenesis, cortisol can break down body proteins and fats so they can be converted into glucose to provide quick fuel for facing a threat. The official term for “break things down” is “catabolism,” making cortisol a catabolic hormone.

Raises Blood Sugar: Low blood glucose (sugar) is a stressor for the body. When blood glucose drops too low, one of cortisol’s jobs is raise it back up using the process of gluconeogenesis mentioned above by converting body proteins and fats to glucose. While being able to convert protein and fat to glucose is an important survival mechanism, this method of raising blood sugar relies on activation of the HPA-axis, or stress response system. This means if your blood sugar frequently dips too low, you are activating your stress response on a regular basis. This is one reason that it’s so important to keep blood sugar balanced with healthy diet and lifestyle choices.

Inflammation: Cortisol has both anti-inflammatory and inflammatory potential. Under acute stress, cortisol can decrease inflammation. However, chronically high cortisol contributes to inflammation, particularly in the central nervous system, which includes the brain (Durque & Munhoz, 2016).

Opposes Melatonin: Together, cortisol and melatonin play a role in when we sleep by regulating our sleep/wake cycle (aka our circadian rhythm). In contrast to cortisol, melatonin is highest at night and lowest in the morning.

Opposes DHEA: While cortisol is a catabolic hormone that breaks things down, DHEA is an anabolic hormone that helps build things up. A healthy ratio of these two hormones helps ensure a healthy balance of catabolism to anabolism in the body.

Autoimmunity: The morning cortisol spike helps kill autoreactive T cells that are still in the thymus gland. T cells are part of your immune system and involved in autoimmunity. T cells go to the thymus to be educated regarding what their job should be before they enter peripheral circulation. Ideally, T cells learn that they should not attack your own body tissue. The morning cortisol spike is when T cells that think they should attack your own body get destroyed. Absence of a healthy cortisol spike in the morning can therefore increase risk for autoimmunity.

Thyroid Health: Cortisol can inhibit both the release of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and the conversion of T4 (inactive thyroid hormone) to T3 (active thyroid hormone) creating a hypothyroid state. The hormone panel I like to gather data with can provide clues about thyroid health by looking at the relationship between free and total cortisol.

What Happens When Cortisol is Dysregulated?

As mentioned in, Why “Adrenal Fatigue” Starts in the Brain, cortisol is released via activation of the HPA-axis and this system was meant for short term stressors (like running away from a lion back in the day). Since your brain doesn’t know the difference between a true threat to your survival and negative thoughts (stressed about work, anyone?), collectively, we have a lot more HPA-axis activation going on than the system was intended to handle. We want cortisol to rise under stress to help us cope, but then we want the stressor to resolve and cortisol to drop again. When we are under chronic stress, our bodies try to pump out extra cortisol until the system starts to dysfunction and you no longer produce enough cortisol to keep up with stressful demands. This dysregulation can lead to a wide variety of symptoms. Following are symptoms of both high and low cortisol:

Symptoms of High Cortisol

Immune system suppression

Slow wound healing

Poor memory

Anxiety

Increased belly fat

Poor sleep

Hyperglycemia

Water retention

Muscle wasting/decreased muscle mass

Decreased bone density

Symptoms of Low Cortisol

Fatigue

Pain

Hypoglycemia

Dizziness or being lightheaded

Low stress tolerance

Depression

Brain fog

Salt cravings

Hypothyroidism

It’s common to have symptoms of both high and low cortisol. While cortisol is supposed to be high in the morning and low at night, sometimes this rhythm gets reversed leading to lower output during the day and higher output at night. Someone with this presentation might be tired and overwhelmed during the day but then feel wired and unable to sleep at night. If your cortisol is dysregulated, you always have to ask yourself, “why?” Hormones don’t become dysfunctional for no reason. Something is triggering your HPA-axis more than it should. It might be work stress, gut infections, emotional trauma, environmental toxicity, or food sensitivities as just a few examples.

REFERENCE

Ref 1: Durque, E.A., & Munhoz, C.D. (2016). The pro-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids in the brain. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 7(78).